Maurice Wood

Maurice Wood, who died on 4th July, 1960, suddenly and without having been seriously ill, at the age of 76, wrote some years ago an autobiographical sketch ‘Sleight’s Farm’ (Star and Furrow, Spring 1957). He speaks there about a turning point in his life. when he was 42 years of age. Now that we can look back over the whole long and very rich life, we can see how this first period gave the background for what came to fruition later, gave Maurice Wood the tools of which he made such wonderful use.

Maurice Wood, who died on 4th July, 1960, suddenly and without having been seriously ill, at the age of 76, wrote some years ago an autobiographical sketch ‘Sleight’s Farm’ (Star and Furrow, Spring 1957). He speaks there about a turning point in his life. when he was 42 years of age. Now that we can look back over the whole long and very rich life, we can see how this first period gave the background for what came to fruition later, gave Maurice Wood the tools of which he made such wonderful use.

Maurice Wood was born in Yorkshire and this stamped his whole life. There was hardly a meeting or longer conversation in which he failed to mention his Yorkshire background, even if not in so many words – Yorkshire was present in manner of expression, in his certainty and sureness, and however annoying it could be for a fleeting moment, one began to appreciate and love this Yorkshire as represented by him.

Maurice Wood was born in Leeds, and he tells us that very few farmers appear among his ancestors. He came from a city where his father owned much property and was a building contractor. All his sons had to learn one of the parts connected with the building trade and Maurice chose bricklaying and stone masonry. Thus he learned to love the stones of the earth and out of this love he could fashion them. He could dress stone so that the product of his labour could form an integral part of a larger plan, full of beauty, full of usefulness. Did we not all recognise these faculties in Maurice Wood in later life? – when he went searching here and there, discovering a picture he needed, a formulation which expressed what he had in mind. And painstakingly he would piece all this together – the bricklayer. But when the essay or lecture was presented the stonemason had been at work, fitting the fruits of his labours into the whole of a conference or into the continuity of common study.

Maurice Wood was born into a Quaker family: he was educated at the Friends’ schools in Ackworth and York. To those of us from other countries (whose only knowledge of Quakerism was perhaps based on the school meals provided by the Society of Friends when Central Europe faced starvation during the blockade after the World War), Maurice Wood was a wonderful revelation of what the Society of Friends stood for. The writer well remembers when he took him to the First meeting and helped with explanations. During the First World War, Maurice Wood worked in Holland in connection with the Friends’ War Victims Relief Committee. Throughout his life he maintained those standards of dealing with business one associated with the Friends, it seemed one of the integral factors of his life.

In 1904 Maurice wood had gone to Canada to work there as a bricklayer for a year. On returning home he set up in business on his own as an estate agent, and also got married, and for more than fifty years it was really Maurice and Etta Wood that one met. After his return from Holland, it seemed impossible for Maurice to go back to his old life, successful as it had been and he took the drastic step of leaving tho city and buying a small farm at Huby between Leeds and Harrogate. He marshalled all his resources and all his courage to start this new life. IN the article mentioned, he tells vividly of his feelings and doubts and determination at that time. He became do Poultry farmer and made a success of it, until he was caught up in the maelstrom of mechanisation. Things began to go wrong and what had been a constructive life, became a nightmare of worries day and night. It resulted in a breakdown from exhaustion, laying him up for weeks. Into the period of convalescence fell that event which was the turning point of bis life.

During his wartime work in Holland, he had met a friend who now invited him e Anthroposophical conference at Glyngarth! on the Island of Anglesey. He became a member of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain, and thus it came about that George Adams stayed with the Woods at Huby while translating who lectures on agriculture which Rudolf Steiner had given in Koberwitz, at Whitsun 1924. That must have been a tremendous fortnight for all of them for George Adams, the brilliant and sympathetic translator who had been Rudolf Steiner’s interpreter for years, to be able to undertake this difficult task while living on a farm. So much better a setting than a study in town: for Maurice Wood to meet these lectures for the first time, not as a printed book but in instalments day by day, as he came in from the fields. Immediately the Yorkshireman and the craftsman in him responded, helped by the singleness of purpose of the Quaker and all the enthusiasm given to the pupil of Spiritual Science, and he set to changing his poultry farm into a balanced holding, turning it into a farm organism. A task fraught with difficulties, as the land was not in one piece, there was an odd field here, another there.

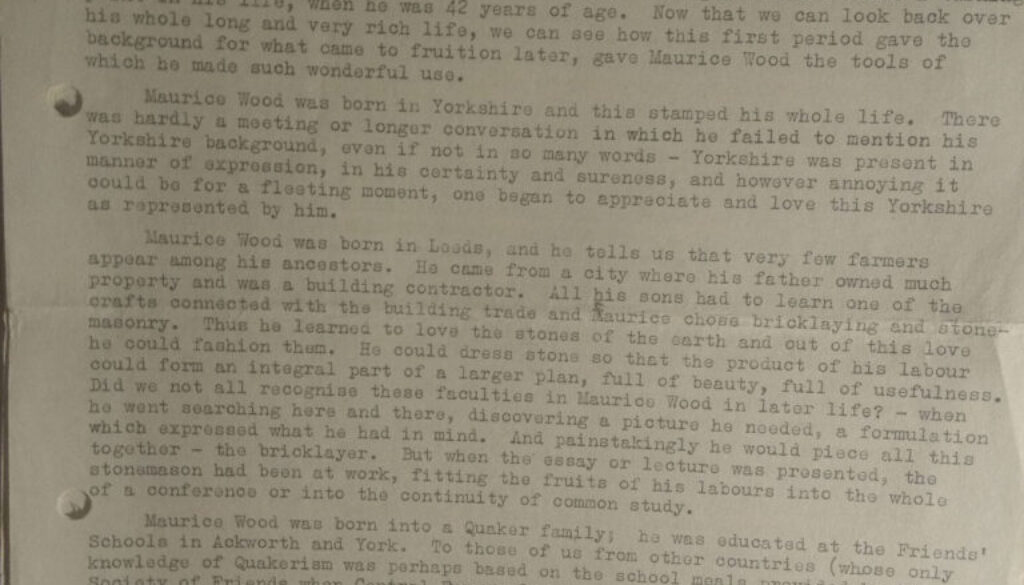

It was in this period that the writer had the privilege of staying at Sleights Farm, first as a guest for six weeks in preparation for the World Conference for Spiritual Science and its Practical Applications, held at the Friends Meeting House in London in 1928, and then for many months during the initial period of the implementation of Rudolf Steiner’s agricultural impulse in this country. With truly Anthroposophical enthusiasm, tempered by the Yorkshireman’s cautious shrewdness and realism, he set to work, concerned with his own farm, but always seeing at the same time the needs of others, most anxious to give his best in the service of Anthroposophia. From the day of that memorable meeting in London, when the foundation was laid of the Bio-Dynamic Movement in this country Maurice Wood has been one of its main pillars, even if, in the course of the years, his functions in the Movement have changed. Work on the farm took precedence and great strides were made. His reputation as a farmer grew and he held office in the local National Farmers Union which grew under his chairmanship. He went to endless trouble at the same time to become a farmer, not by ‘going back to nature’ but by living in accordance with the true demands of the time. There were week-ends devoted to the deepening of knowledge of Spiritual Science, there were visits from leading Anthroposophists from Britain and abroad, there were visits to conferences and meetings, there developed a steadily growing correspondence with anyone who he felt could or should know of and understand Rudolf Steiner’s gift to agriculture.

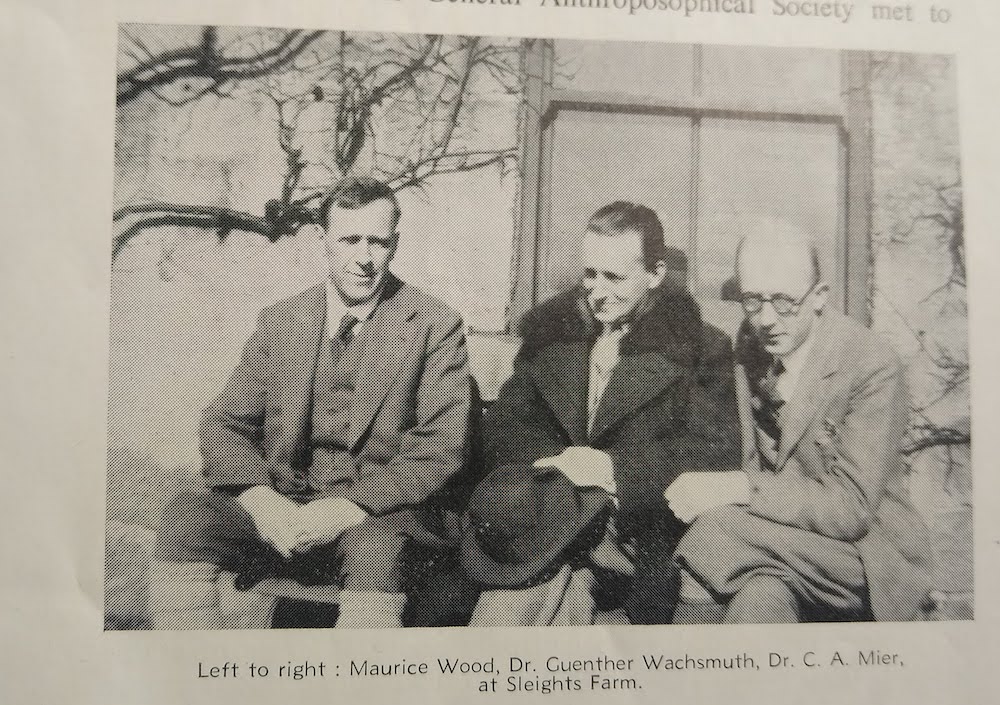

When war broke out, he found himself at times at cross purposes with the authorities and their directions to farming. They found their match in Maurice Wood who would not act against his better knowledge and his convictions. Over the years he also took a growing interest in how his products, especially his corn, could reach the consumer – and so he became a miller. To see Maurice Wood stooping over his ‘Huby Mill’ was a revelation of the man and also an unforgettable lesson. How he loved his millstones and the patterns of their dressing. He made models so that also those “unfortunate” people who were neither faemmers nor millers night understand what happens inside a mill. For he loved to handle The Corn and ascertaining its moisture, not with instruments, just with his hands. How he watched that mysterious change from corn to flour. Here again he fought for his principles, and when his small mill was to be prevented from milling grain produced on his own farm, the case was carried right to the House of Commons. Maurice Wood got his way and in the article quoted the text of the Official reply in Parliament is given, followed by the words: “Actually, I had only 30 cwt of wheat of my own growing that year…” How he must have chuckled when he got the official reply – and when he wrote about it.

When war broke out, he found himself at times at cross purposes with the authorities and their directions to farming. They found their match in Maurice Wood who would not act against his better knowledge and his convictions. Over the years he also took a growing interest in how his products, especially his corn, could reach the consumer – and so he became a miller. To see Maurice Wood stooping over his ‘Huby Mill’ was a revelation of the man and also an unforgettable lesson. How he loved his millstones and the patterns of their dressing. He made models so that also those “unfortunate” people who were neither faemmers nor millers night understand what happens inside a mill. For he loved to handle The Corn and ascertaining its moisture, not with instruments, just with his hands. How he watched that mysterious change from corn to flour. Here again he fought for his principles, and when his small mill was to be prevented from milling grain produced on his own farm, the case was carried right to the House of Commons. Maurice Wood got his way and in the article quoted the text of the Official reply in Parliament is given, followed by the words: “Actually, I had only 30 cwt of wheat of my own growing that year…” How he must have chuckled when he got the official reply – and when he wrote about it.

Alter the war the farm became too great a burden, with labour and other difficulties, and Maurice Wood concentrated on being a miller. He built up a flourishing business, sending Huby’ flour all over the country. His business acumen helped him to do all this most efficiently. But he had definite views on the size of such a milling enterprise and so he designed the ‘Huby Mill’ for sale to others, and these mills have gone far afield. even overseas. True craftsmanship went into their making, and long before they were despatched he would point to the stones – These will go to so-and-so, that lot to that place. In a way, each mill was built around a pair of stones, personally selected by him in the quarries.

It is characteristic of Maurice Wood’s life that it stands before us as a whole. There is only that one turning point when he met Rudolf Steiner’s work. Otherwise there is always this gradual foreshadowing, this incipient growth of something new while the old phase is still active. And when the time came when age made it necessary to give up active physical work as a miller, he had trained someone whom he helped to set up in business as ‘Huby Mill’, but no longer at Huby, but some miles away. For Maurice Wood there started that last phase of his life studying, writing, counselling. Ever since he joined the bio-dynamic work, he liked to write and he wrote so well. We have from his hand a lovely essay, “Man and the Feathered World’, inspired by his deep study of Rudolf Steiner’s lectures on Man as the Symphony of the Creative World; later he wrote much about the grain, on minerals, and many other topics. The list of his writings is surprisingly long and covers an astonishing range of subjects. This last phase of his life brought so much to fruition, summed up so much of his life’s striving, and was also most characteristic of his whole being. He had become rather deaf and much as he suffered from this impediment to free and easy contact with others it also gave him the opportunity of not hearing what he did not want to hear, and yet he listened most modestly. Altogether, his humility often put us younger ones to shame. In his studies he would pick a subject, a theme (and the writer was one of those who would ask: ‘What on earth makes Maurice pick on this! – only to see much later how it fitted into a grander and wider theme). and then he would read widely, in Anthroposophical and other literature. He had that strange gift of being able to pick up the most learned and weighty tome and find among its hundreds of pages just the one illustration or passage he needed. When he did this, one somehow saw the Yorkshire stonemason picking up a stone, turning it over and over, and then carefully setting to work until under his loving treatment it fitted in just where he wanted it to rest, as ornament or as support.

During the last years of his life, his whole love and most of his thoughts belonged to the Experimental Circle of Anthroposophical Farmers and Gardeners. He moulded its present form and he gave of his best to keeping the members together.

Most of us have never met Maurice as a young man, he was always mature. For years we knew him as an old man, one would almost say The Old Man. But he showed the most beautiful attributes or old age, experience, wisdom, love, perseverence, courage, humour, mildness, humility and readiness to hand over his work to others where he could no longer act. To have met Maurice Wood was an experience not easily forgotten, to have been associated with him in work gave standards not easily maintained to have been called his friend (and there are many) makes us feel his passing as a cruel loss and, at the same time, fills us with gratitude for having gained his friendship, and with resolve to let this friendship bear fruit.