George Corrin

It was Carl who invited George Corrin to attend a Circle Conference. I shall always remember how, at the end of the conference, he got up and thanked the Circle for inviting him, saying his life would never be the same again. George, a very intelligent man, had opted out of “civilisation” and lived on a small holding with his wife in mid-Wales saying he wanted to bring up his children on healthy foods and true human values. On Carl’s moving up to Camphill Scotland and later becoming one of the pioneers of Botton Village, we asked George if he would be our consultant; so began a long and most fruitful collaboration.

_____

“Visits to Clent around Michaelmas are mostly involved with making the B.D. preparations for which I have been responsible for around twenty-five years. In this work the greatest praise must go to Miss Joey Williets for all her help in the actual making of the preparations and her careful dispatch of them. In the last few years Tim Clement has spared time from farm work to make preparations for Broome Farm and assist with those for members. Other friends have assisted in gathering the plants – the man-hours involved in this operation are quite astronomical. This year, I travelled down to Cornwall where great drifts of valerian grow along the banks of the river Camel. I had a large mincing machine, which I had converted to electrical drive with an old washing – machine motor, and a fruit press in the back of the Escort. I spent two mornings with Marjorie and John Soper, and John’s sister picking the flower heads and in the afternoon and evening extracting the juice. I have seen no similar expanses of valerian in Worcestershire, Shropshire or Powys.”

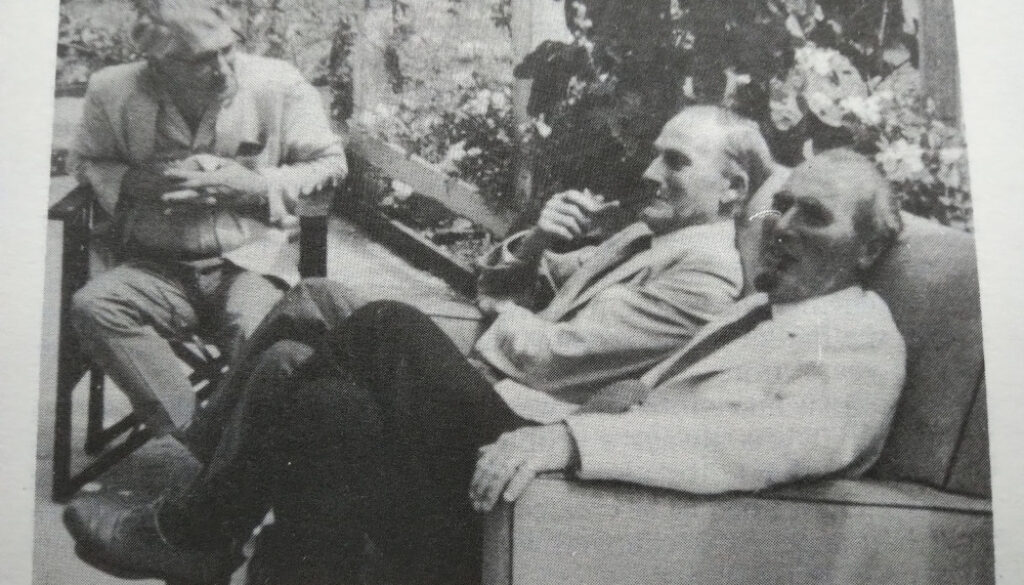

George Corrin 1979

GEORGE CORRIN – AN APPRECIATION

Alan Brockman

Perhaps some members will not have heard the sad news of the death of George Corrin on 18th February 1994 in Shrewsbury. George was the consultant for the BDAA for many years and was well known both personally and through his Members’ Bulletin which appeared twice yearly.

His Handbook on Composting and the Bio-Dynamic Preparations (1960) followed on his work in bringing out the revised edition of Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture course in 1958. It is difficult to convey the impression George made on one. He was extremely well read in his field and had a very penetrating perception of current trends in conventional farming. His sense of humour had something impish about it. He would often make a remark, look at you with wide blue eyes, trying not to laugh, to see if you thought things were as crazy as he thought them.

I first got to know George in 1954, on the spring tour of Dutch and West German biodynamic farms and gardens organised by Carl Mier. He was then 33 years old and was closely connected with Maurice Wood one of the first BD farmers in England. Maurice had a most enquiring mind and George’s interest owes quite a lot to Maurice’s inspiration.

We attended many international BD conferences at Dornach in Switzerland and although I never heard George say very much in German he had an almost intuitive sense of how to put people at ease. George was never one to be carried away by ideas and, I think, found it hard when someone waxed over-enthusiastic about something or other. He could, on occasion, bring things to a head, which didn’t always lead to harmony. One respects a person more sometimes for speaking out if need be.

At conferences, especially of the Experimental Circle, washing up was invariably led by George who kept things very much on the move with example or wit. I think we probably enjoyed our washing up as much as the rest of the conference. George had a wide heart and could feel very much for others. The reverse side meant that he could take things very much to heart on occasion.

For many years David Clement, John Soper and George formed an executive group which did most of the spade work to keep the BDAA running. With a small association and limited resources it was only the dedication of the three ‘Broome Heads’ as one member affectionately referred to them, that pulled us through. (The BDAA office was then situated at Broome Farm, near Clent.)

There are many eddies in the river of life where individuals come together for a time to create something new or do something which needs to be done and then go their own separate ways to other tasks. I feel that the work that David, John and George did together for so long, both in the BDAA Council and in the Experimental Circle, has bridged the gap between the original founding impulse of the biodynamic movement in this country and the new initiatives which are now unfolding as we approach the end of the century. George will, I am sure, be with us all in our biodynamic impulses and initiatives. I was able to be present at the simple vet wonderful funeral service in Shrewsbury. The flowers and sunshine seemed somehow to reinforce the feeling that George would have us all wake up and love one another more.

I feel that all those who knew George will remember him with affection and wish him well.

TRUTH IN AGRICULTURE

George Corrin

This article, reprinted from Star and Furrow no. 8, Spring 1962, is included here in memory of George Corrin (17 Dec. 1921-18 Feb. 1994) and his invaluable contribution to biodynamics in Britain. Its contents seem as pertinent now as they were thirty-two years ago.

I am not by nature an historian. To me the intrigues of kings, queens, politicians and generals make a far less interesting story than the life of the earthworm. Yet, in trying to understand the significance of biodynamic agriculture, I have had to look back into the history of agricultural ideas, and learn something of the men connected with them. Forgive me, then, if I inflict a history lesson on you. I am not going to deal with the history of agriculture from primeval times, not show how the prevailing scientific, cultural and social conditions were reflected in agricultural practices. My aim is much less ambitious; 300 years will suffice for my purpose.

In 1648 Van Helmont planted a 5lb. willow in 200lb. of soil, and although it only received water, at the end of five years the willow weighed 691b. 3 oz. He concluded, “Water alone had, therefore, been sufficient to produce 641b. of wood, bark and roots,” and so assumed that plants were made entirely of water. Some 150 years later Jethro Tull wrote, “Every plant is earth, and the growth and true increase of a plant is the addition of more earth.” He suggested that if by tillage the soil was pulverised so that its particles were made fine enough to be taken in by the plant roots we could be assured of lasting fertility in spite of the quantity of dung being limited.

At about the same time on the continent the idea that the carrier of the life force was humus held sway; an infertile soil was attributed to a lack of humus. Two very different men were the prophets of humus. Albrecht Daniel Thaer is often thought of as the father of rational agriculture. He maintained that the first purpose of agriculture was to make money, and the way to do this was to rely on rational ideas. One of his rational ideas was that humus was the sole source of nourishment for plants, and that humus is absorbed directly through the roots.

Seven years younger than Thaer was Johannes Nepomuk Schwerz, who, although not a trained agriculturist, took over the management of an estate when he was 42. He was a devout Catholic leading an almost priestly life. Unike Thaer he mistrusted reason, prefering to rely upon experience. Whereas Thaer wanted to master Nature, he make the desert fertile, Shwertz preferred to let Nature be the leader; he was prepared to help but not to master: In 1818 he was appointed to the new agricultural institute at Hohenheim, and put into practice his idea of the small self-contained farm relying on manure to maintain its fertility. “Dung is gold” was his guiding idea.

A conflicting opinion was expressed by Theodore de Saussure, of Switzerland. Pursuing quantitative studies of air, water and plant growth, he pointed out that the ash of plants was derived from the soil materials.

This idea was not acceptable to the great English chemist Humphrey Davy, who in his “Elements of Agricultural Chemistry” maintained that the inorganic elements in the soil merely act as stimulants; the true food for plants is organic matter.

Lecturing in Paris in 1823, Justus von Liebig met Alexander von Humboldt, and attributes the direction of his life’s work to this meeting. Humboldt was a man of wide interests, in contact with the leading scientists of his time in many countries. Following the researches of Galvani he felt that the new discoveries in electricity gave the key to the understanding of life, and that the fullest application of the various sciences could lead man forward into a new era of freedom and prosperity. These ideas captured Liebig’s imagination, and as one of his ideals was to save man from starvation he was delighted to put his knowledge of chemistry at the service of agriculture. By analysing the ash of plants Liebig was able to say what quantity of minerals the plant had taken from the ground, and therefore how much poorer the soil was in mineral matter. His aim was to produce plants by way of the soil; he wanted to preserve soil fertility; he nad no wish to rob the soil. Therefore the minerals that had been removed must be replaced by some means.

It was unfortunate for the upholders of the humus theory that the yields at Hohenheim fell after about 10 years under Schwerz’s “Golden Dung Husbandry”, for this added weight to Liebig’s contention that the Hohenheim system was a form of “export husbandry” – plant and animal substances were sold of the farm but the loss of minerals was not made good. It should not be thought that Liebig had no idea of the value of dung. He was well aware of the continuing fertility of the oriental gardens through intensive inter-cropping, and the use of faeces and earth in compost. He saw in this system a method whereby the fermentation process in the compost heap released the minerals from the added earth, etc., so that they could be absorbed by plant roots. Why not short-circuit this time-consuming and laborious process by applying the minerals direct?

In the preface to his lecture to the British Association in 1840 we read, “…The primary source whence man and animals derive the means of their growth and support is the vegetable kingdom. Plants on the other hand find new nutrition material only in inorganic substances.”

This statement dealt a death-blow to the humus theory, and for over 100 years this statement of Liebig’s has been the foundation of agricultural chemistry, and the basis of which advice has been given for manuring with artificial fertilisers. Perhaps this was inevitable in a commercial world. Manufacturers were glad to be able to sell their once useless by-products as artificial fertilisers, or to set up works to make use of electricity to produce cheap nitrogenous fertilisers. Big business has little sympathy with ideas that cannot be turned into money. Producing humus on your own farm by good husbandry is not the kind of activity to interest the man with an aptitude for buying and selling, and an eye on quick profits.

Perhaps, too, this was why another man living at the same time as Liebig was not listened to, his ideas were not an economic proposition. In Holland lived Gerrit Jan Mulder with a degree in medicine and pharmacy teaching in the medical school at Rotterdam. Enforced retirement as the result of a nervous breakdown gave him the opportunity to study chemistry, and he formulated ideas on the nature of protein and its importance for human beings. He then turned his attention to agricultural chemistry and published a four-volume work on The Chemistry of the Cultivable Soils. He could not accept Liebig’s theories but stated that the soil regulates the action of the plant to fertilisers, and that it is not the plant that is fed but the soil, for which purpose we need humus. No opportunity here for the manufacturer and high-pressure salesman. His ideas were not accepted and Liebig reigned supreme. Mulder engaged in bitter controversies and ended his days in loneliness, and blindness, and with a heart disease.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century yet another man queried the practices evolved from Liebig’s theories. This was Dr. Julius Hensel. He was not satisfied that looking after the nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and calcium status of the soil would ensure lasting fertility. It is an axiom of Liebig’s teaching that the growth of the plant is determined by the mineral least available. That is to say, it doesn’t matter how much nitrogen and phosphorus are present; if there is insufficient potassium you cannot get optimum plant growth. On the other hand if there is no shortage of potassium but one of the other elements is lacking, then growth will still be stunted. This is often summed up as the Law of the Minimum. This is all very well, thought Hensel, but there may well be other elements necessary for plant growth, and they are not being added. Continued cropping is bound to deprive the soil of these. The time must come when there will be a minimum of some of these minor elements, and plant growth will suffer. Now he had noticed that where streams carrying water from the mountains deposited substance on the valley floor, there the plants grew well and were healthy; where no new alluvial soll was added the land gradually became exhausted. From this observation arose his plan to powder the primeval mountain rocks and spread them on soil where Nature was not taking them. People could not understand how this “useless dirt” could help. To them he was yet another crazy person.

Early in this century Rudolf Steiner gave eight lectures at Koberwitz, in Silesia, and admitted that some of the ideas would seem crazy. Students of those lectures will have observed that I have already mentioned certain ideas familiar to them in those lectures – the importance of humus (Thaer, Schwerz, Mulder), the self-contained farm (Schwerz), manure the soil, not the plant (Mulder), plants do not live by NPK alone (Hensel), thẻ importance of protein (Mulder). All these ideas are to be found in the lectures but have been advocated by teachers before Rudolf Steiner spoke about them in 1924.

What then did Rudolf Steiner add to our farming outlook? That a purely earthly viewpoint was not enough; that cosmic factors had to be taken into consideration; that substance was created out of the cosmos; that we speak truly of matter only when we realise that it is created by the spirit; that spirit penetrates into the essence and activity of matter, and Preparations were indicated to further this process. Samuel Hahnemann had already shown that infinitely high dilutions of substance could affect the human organism. But here was Rudolf Steiner stating that specially prepared substances infinitely diluted could be used as manure. I doubt whether we can fully realise the impact these statements must have made on that audience at Koberwitz, for almost 40 years later we are more aware of the power of forces than were the men of the 1920s.

Yet it would be a grave mistake if we allowed ourselves to attach undue importance to spiritual forces and give the impression that material substance was untouchable. This would be to fall into the error of teachers and pupils of the past. Isn’t it a characteristic of their behaviour that having grasped an aspect of truth they have become blinded to all else? Of course Hensel was right, rocks are broken down and plant life can live on them but only if there is microbial and bacterial activity there first; adding finely ground rock to a dead soil will not help. Of course humus is essential for plant growth as Thaer, Schwerz and Mulder advocated but it must be the correct form of humus, and other ground conditions must be satisfactory before we can grow the plants we require there is plenty of humus in a peat bog but other conditions are not suitable for growing wheat, say. Of course nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and calcium are necessary for plants to grow. Liebig was quite correct when he stated this but other forms of nourishment are also necessary if plants are to be healthy and provide suitable food for man and beast. These limited viewpoints are not enough.

I have no doubt that if you put me in a clinically clean cell, and fed me calculated amounts of protein, carbohydrate, vitamin pills and water I would live, or rather exist, for some considerable time. Under such conditions I would crave for the taste of fresh fruit, or a sprinkling of herbs with my food; I would long for the sight of the changing colours on the chills, the soul-refreshing effect of music, and all the other imponderables of contact with human culture. I would crave the totality, and find the one-sided, narrow approach unendurable; for life to continue there must be a balance between all the forces of earth and cosmos. We see the obvious need of balance in a machine; any unbalance in a dynamo revolving at speed would set up vibrations sufficient to wreck the machine. Isn’t this seeking after balance equally desirable in human life? The healthy life consists of a dynamic balance between soaring into the fanciful, the mystical, on the one hand, and being drawn down into the materialistic on the other; or a balance between the hot-blooded and the indolent.

Let it not be thought that intensive use of the biodynamic preparations and sprays will do away with the need for manure. Manuring is not only a question of forces and energies but also of matter, and if you have ever cleaned out a cattle yard and spread manure with a fork, before the era of foreloaders and mechanical spreaders, you’ll know what heavy material manure can be, and how very strong is the force of gravity! No, the two must go together. In fact, it is this realisation of the need for so many diverse factors working together that makes biodynamic agriculture such a fascinating study. That this is the way to produce food of a quality fit for the complete nourishment of the whole man becomes increasingly obvious. That one is treating the soil, or the earth, in keeping with its true nature is profoundly satisfying, for one knows that it is not being exploited for selfish gain but that the fertility is being maintained or increased by careful attention to the humus content of the soil through sound crop rotations, use of organic materials in composts, the use of phosphate rock or limestone where necessary, sound animal husbandry, and an awareness of the ecological requirements of a district. It may well be said that there is nothing new in all this, that people have been doing some of these things for years. That is true. What is significant is that the biodynamic method provides the clue to bringing these diverse ideas together to form a totality, a unity.