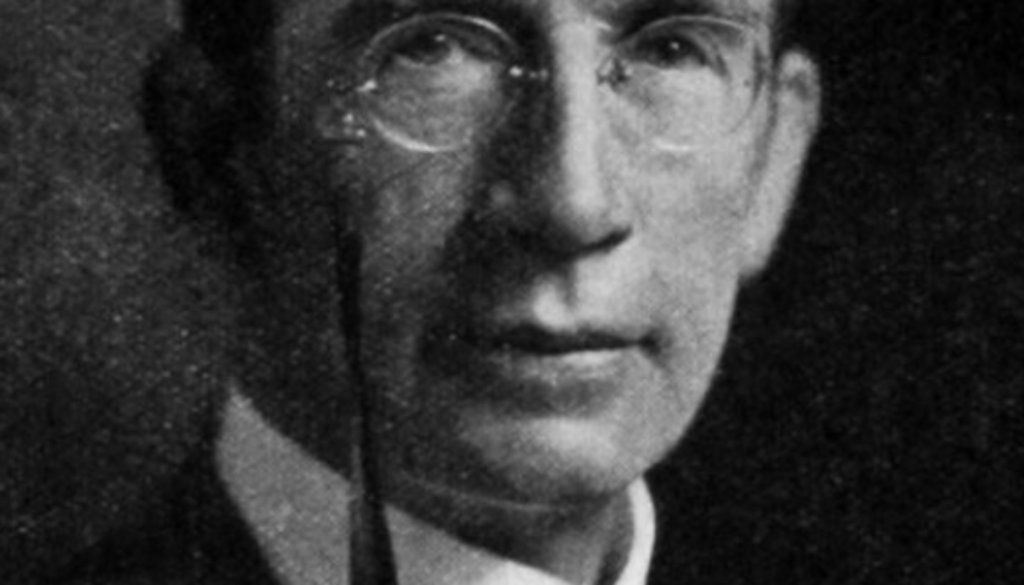

D N Dunlop

1868 - 1935

Daniel Nicol Dunlop “(28 December 1868, Kilmarnock, Scotland – 30 May 1935, London) was a Scottish entrepreneur, founder of the World Power Conference (image available here) and other associations, and a theosophist-turned-anthroposophist.

Dunlop saw Rudolf Steiner for the first time while the latter was still General Secretary of the German Section of the Theosophical Society. He did not, however, join the Anthroposophical Society until 1920, at which time he called into being the anthroposophical “Human Freedom Group”, which he led. Here once again, he introduced the idea of, this time, anthroposophical Summer Schools that were realised in 1923 and again in 1924. After personally meeting with Rudolf Steiner, both of them expressed their intimate spiritual connection and respect for one another. In 1928 he organised the first and only World Conference on Anthroposophy (which bought BD to the UK for the first time) and in 1929 he was elected General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain. He was on terms of intimate friendship with Eleanor Merry (1873–1956), who supported his work, especially after the death of his own wife, Eleanor in 1932. As a result of conflicts and power struggles within the General Anthroposophical Society, leading to its splintering in April 1935, Dunlop was expelled together with a number of other leading members. He died shortly afterwards of an appendicitis. Dunlop enlisted the help of fellow anthroposophist Walter Johannes Stein in the hope of founding a World Economic Organisation, but his death prevented this.”

Dunlop started the AAF and the UK Experimental Circle. He was persona non grata after the split at Dornach

WJ Stein wrote an appreciation of Daniel Dunlop

Thomas Meyer wrote more

_______________

Remembering Daniel Dunlop (1868–1935)

During the Christmas Conference refounding of the Anthroposophical Society, Rudolf Steiner remarked Daniel Dunlop’s absence. One can speculate about the reasons, which were in part linked to internal challenges within the Anthroposophical Society, but that is not where I would like to place the focus.

Theosophy and electricity

As the World Power Conference website makes clear, one hundred years ago a major event was being held in London, with thousands of delegates from all over the world, opened by the then Prince of Wales, who became the short-reigning Edward VIII. All due not only to the initiative of Daniel Dunlop, but to his organising skills and his being embedded in the business world of the day. If one runs the clock back from that event six months, it is not surprising to find him staying in London during the Holy Nights 1923/1924.

Nor is it surprising to see him putting on such a gathering. Long before his meeting with Rudolf Steiner his destiny linked him to the theosophical world, to the United States, and to the fledgling world of industrial electricity. Just as Rudolf Steiner can be imagined as heading West, so Dunlop came out of the West to meet him. Dunlop’s ground, in other words, was his own. He did not go out of anthroposophy into western economic life. Indeed, I doubt one can.

Rather, in the world of active entrepreneurship – especially in ‘the West’, which for Dunlop is perhaps better described as ‘a place beyond Hibernia’ – one always knows the limits of one’s consciousness and how ideals of altruism are all the time challenged by and often snagged on one’s own egotism, ‘clubby’ behaviour, narrow Newtonism and entrenched Darwinism. Not to mention the subtle underlying supremacist reasoning that is often just under the surface of business life. All this Dunlop would have known and learned to navigate, and all before he met Steiner or anthroposophy. Which is why, in my image, they met as brothers.

‘I’ prevented from being arbiter

Although outer economic developments do not tell this story (except that, having been ‘airbrushed’ out of the World Power Conference’s history, it was reinstated a few years back); nor do they follow up on Dunlop’s seminal endeavours to take stock of humanity’s world resources, but not as national possessions. Only Walter Johannes Stein seems to have kept this flame alive as long as he could. Meanwhile the world, which could have unfolded a worldwide commonwealth out of the British Empire, followed the hegemony of the United States instead, leading us all into what I call the Great Detour; one hundred years of wasted history, unspeakable levels of murder, and a world riven in two, so that the ‘I’ can never be the arbiter of world affairs.

It is this ‘I’ that Dunlop’s being speaks to. It is this ‘I’, the seat and author of egoism enlarged to include the entire human family, that both opens itself to what spiritual science has to say at the same time as it sends roots born of its own existence deep into the ‘soil’ of economic history. Daniel Dunlop spoke to the Dunlop in each of us, the Dunlop who can be found in every truly ‘associative’ economist.

Not missing rare opportunities

This is not to make a hero out of him, so much as a colleague that those who carry the torch of associative economics should always seek out; whose counsel we should heed. Especially, the importance of timing. For, while our endeavours must never cease or falter just because circumstances seem not to be propitious, we would deeply regret deserting our duty if, for that reason, we were not ready were the clouds to open, as well they might, for a brief moment yet long enough to allow a once-in-a-hundred-year flowering of possibility. For there are such plants. Just as they defy the drought of the desert; so, we can defy the drought of history.

Hayek, Keynes and Steiner on one page

Readers may be interested to know, that a recent book of mine has been published: Beyond Gold / Hayek, Keynes and Steiner in Concert, spanning that same period of time, from 1923 until now. Its main thesis is that if the minds of those three economists can come onto one page, at least in the imagination or in the realm of dreams and albeit late in the historical day, the dichotomy that determines all social life today will begin to melt away. But not otherwise.

Christopher Houghton Budd